Baudrillard at the Ballgame: The Tomahawk Chop and the Illusion of Culture

I. Introduction: The Chant That Echoes

I’m sure most of us are familiar with the infamous “Tomahawk Chop” - that rhythmic chant still echoing through Oklahoma City Chiefs Games, a tradition that dates back to the 1980s. I remember the hype vividly. Watching football, you’d hear it and think, “Look, they’re all ‘playing Indian’ in the stands.” It’s catchy, right? That hypnotic descending tune, the pulsing beat: “oh-o oh-o-o, oh-o-o, oh, oh-o-o.” It sounds unmistakably “Indian” … or at least that’s what we’ve been led to believe.

But where does that sound actually come from?

To many, including myself at one time, that melody fits perfectly into the familiar catalog of so-called “Indian” music - the same category that includes the “hey-how-are-ya” chants or the classic Western movie trope of ululation, where kids tap their mouths with their hands and mimic an exoticized war cry. We all grew up with this version of “Indian” music.

And yet, what if I told you this music has little to no connection to real indigenous musical traditions of North America? What if I told you this genre is not an authentic representation, but rather a carefully curated myth - a stereotype that’s been repackaged over time by Western composers? It’s not just appropriation; it’s a distortion. As modernist philosopher Jean Baudrillard might put it, it’s a simulacrum - a hollow imitation that replaces reality with a constructed image. Things get even more complicated when people who identify as Native American seem to support or embrace these portrayals, which makes it harder to call them out as inauthentic or harmful without stepping into a really tricky grey area.

So, Why the long Intro? And why tackle such a sensitive topic? Well, in my research on silent film music, I kept stumbling across something that caught my ear - the recurring use of the “Indian” (or Native American) musical trope. Time and again, I’d listen to these old scores and think, “Wait a second… this sounds a lot like the Tomahawk Chop.” The sports chant, which didn’t really take off until the 1980s, echoes music written nearly a century earlier - music that was part of a broader movement to represent Indigenous identity through a Western lens.

Naturally, I started asking questions. How has this musical stereotype lasted so long? Why do the melodies sound so similar, despite the decades between them? It felt too consistent to be coincidence. The more I researched, the more I saw a clear through-line connecting early 20th-century silent film scores to the Tomahawk Chop we sadly still hear in stadiums today.

That realization opened a bigger door for me - one that led to questions about Americana itself and how deeply these distorted representations of Native culture are embedded in American popular music and identity. So, in this post, I want to explore and argue that the Tomahawk Chop didn’t come from authentic Indigenous traditions, but from a long legacy of media-driven musical simulation - a lineage that stretches back to silent films and turn-of-the-century concert music.

By the end of this blog, I hope to make a clear case for how the “Indian” trope in music evolved - not from Indigenous traditions, but from a long history of cultural distortion. I’ll trace its origins back to the late 19th century, starting with the publication of Alice Fletcher’s work on Native American songs and stories. Her collection, while groundbreaking in its time, played a major role in abstracting and codifying Indigenous music into forms more digestible for Western ears.

From there, I’ll explore how the popular “Cowboys and Indians” narrative became deeply embedded in American culture, especially through literature, silent film scores, and popular music. That trope, so central to the idea of Americana, helped solidify the stereotype of “Indian Music” - a version that later found its way into American sports culture, particularly in the Tomahawk Chop. Then I’ll step back and get a bit philosophical, drawing on Jean Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra and simulation to argue that what we now recognize as “Indian Music” is, in fact, a simulation. A simulation so thoroughly repeated and visualized that it’s come to feel real- not just to non-natives, but in some cases, even to Native communities.

And finally, it’s crucial that this conversation includes Indigenous voices. They are, and should always be, the ultimate authority on how their culture is represented and interpreted. This blog is meant to be a conversation starter, not the final word.

II. Origins: Ethnographic Echoes and the Birth of the “Indian Sound”

There’s always been a fascination, sometimes respectful, often problematic, with Indigenous cultures in America, going all the way back to the first encounters during colonization (or let’s be honest, invasion). From the start, European settlers, especially Protestant English colonists, viewed Native people through a skewed lens. They were seen not as complex human beings with their own sophisticated societies, but as “savages.” That word “savage” actually comes from Old French, meaning “wild” or “of the woods,” something untamed and supposedly lacking control or refinement.

Through the eyes of these settlers, Indigenous ways of life were labeled as primitive, especially when compared to what they saw as their own “civilized” Christian values. That sense of superiority fueled not just religious missions to convert Indigenous cultures were often looked down upon, not as different, but as deficient.

Because of this perspective, early European curiosity quickly turned Indigenous people into subjects of spectacle. Literally. Native individuals were brought to Europe and displayed like living museum pieces; a kind of ethnographic sideshow. Imagine the whispers in the crowd: “Look at how primitive they are! They hardly wear clothes!” It’s uncomfortable, but it’s true. This exoticized, dehumanizing view of Native cultures stuck around for centuries, shaping public opinion and cultural stereotypes for generations.

By the time the 18th century rolled around, something interesting started to happen. According to the author Philip. J. Deloria in his book Playing Indian (1998), the settlers, who had long viewed Native Americans as outsiders, began to feel a kind of unexpected kinship with them. Why? Well, tensions with the UK were growing worse by the day, and the settlers started to see themselves not as polished Europeans anymore—but as people shaped by the wild, untamed land around them.

They began to relate more and more to what they once called “savagery”—not in a negative sense, but as a symbol of survival, grit, and living off the unpredictable wilderness. Life in the young colonies was hard, full of unknowns and daily struggles, and the settlers found a new identity that felt more real than their old ties to Britain.

Things began to shift again in the mid-19th century, when the study of Indigenous cultures finally started to take on a more academic and (somewhat) respectful tone. One important figure in this change was Alice Fletcher. Born in 1838 in Cuba, Fletcher was an American ethnologist who dedicated much of her career to studying the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains.

Fletcher gained the trust of several tribes and was allowed to observe their rituals and document their music; a major step in preserving cultural traditions that were, by then, already under threat from assimilation policies. In 1893, she recorded wax cylinders of audio of the Omaha and Osage tribes, some of the earliest sound recordings of Native American music. These recordings are now housed at the Peabody Museum and are even available to the public through the Archive of Folk Song at the Library of Congress.

One of Alice Fletcher’s major contributions to the field was her publication, Indian Story and Song from North America, published in Boston in 1900. It wasn’t just a book of transcriptions; it was a deliberate attempt to present Indigenous music in a way that both musicians and the general public could access. Most of the songs in the book were harmonized by Professor J.C. Fillmore, while some were transcribed directly from early graphophone cylinder recordings by Edwin S. Tracy along with background stories.

One particularly unique moment Fletcher shares in the book is the performance of traditional Omaha songs at the Congress of Musicians during the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha, July 1898. Imagine that: Native performers singing their own music for an audience of Western-trained musicians. That kind of cross-cultural presentation was rare, and it left an impression.

In the preface, Fletcher explains why she chose to include not just the music, but also the stories behind the songs. She writes:

“It was felt that this availability would be greater if the story, or the ceremony which gave rise to the song, could be known, so that, in developing the theme, all the movements might be consonant with the circumstances that had inspired the motive. In the response to the expressed desire of many musicians, I have here given a number of songs in their matrix of story.” (p. vii)

In other words, Fletcher understood that music doesn’t exist in a vacuum. She believed that the full meaning of a song only becomes clear when you know the context that inspired it. But despite her effort to preserve that connection, the melodies she documented were eventually stripped from their original stories and repurposed into something else entirely; part of the broader “Indian” musical stereotype we see echoed in things like sports chants and mascots.

Fletcher also had another motive: she wanted this music to reach beyond ethnographic circles and into the hands of composers and performers. She felt that the music deserved a wider audience. As she put it:

“Material like that brought together in these pages has hitherto appeared only in scientific publications… It is now offered in a more popular form, that the general public may share with the student the light shed by these untutored melodies upon the history of music… and reveal to us something of the foundations upon which rest the art of music as we know it to-day.” (p. vii–viii)

That phrase “untutored melodies” says a lot about her worldview. While Fletcher admired the music, she still viewed it through a Western historical lens, almost like she was peering into the distant past of Western music, before polyphony and harmony took over. To her, Indigenous music was a kind of living fossil; valuable, but primitive.

She drives this point home with a final metaphor in the preface, where she writes:

“Aside from its scientific value, this music possesses a charm of spontaneity that cannot fail to please those who would come near to nature and enjoy the expression of emotion untrammeled by the intellectual control of schools. These songs are like the wild flowers [sic] that have not yet come under the transforming hand of the gardener.” (p. ix)

It’s a poetic image … and a telling one. Fletcher saw these songs as raw, beautiful, and untouched by “civilized” musical training. While her intentions were probably respectful for the time, her language reveals the same deep-seated assumptions that framed Indigenous culture as something closer to nature than to civilization — something wild, in need of cultivation, something savage.

Now, if you take a first look at the musical “transcriptions” in Fletcher’s Indian Story and Song from North America, one thing jumps out right away — the melodies are harmonized. That raises an obvious but important question: Did Native Americans traditionally perform these songs with harmony? The short answer? No.

Dig a little deeper, and you’ll find that the harmonizations were actually added by Professor John Comfort Fillmore, an American writer on music and already had the controversial idea that music of all cultures has a harmonic basis in major and minor triads. While some melodies were transcribed from early wax cylinder recordings by Edwin S. Tracy, the harmonies themselves weren’t part of the original songs, they were layered on afterward to suit Western musical sensibilities.

Fletcher herself addresses this in a paper she published in The Journal of American Folklore in 1898 — two years before her book came out. Here’s what she wrote:

“It was true that the unsupported aria did not bring the writer the musical picture of the song as [the author] had heard it given in unison by the Indian singers; her ear unconsciously demanded a few simple chords to sustain the aria, not to modify it, or in any way change it.”

This quote is really telling. Fletcher admits that hearing the melody without chords felt somehow incomplete to her “Western ear.” So she added harmony—not to change the song (or so she believed), but to “sustain” it, to make it sound more familiar or, in her view, more complete.

But here’s the problem: by adding Western harmony, the music was changed.

Harmony imposes a vertical structure, chords stacked beneath a melody, that fundamentally shifts how we perceive the music. Traditional Indigenous music often emphasizes horizontal relationships: the flow of one note to the next, the rhythm, the phrasing. Anyone familiar with modal counterpoint knows that vertical (harmonic) and horizontal (melodic) structures are two very different ways of understanding and experiencing music.

In other words, Fletcher’s harmonization wasn’t just a supportive addition — it was a transformation. It reframed the music in Western terms, making it easier for non-Native audiences to digest, but in the process, it also flattened the cultural meaning and authenticity of the original songs.

Fletcher even tells a story to support her decision:

“One day she so played a choral of the Wa-wan ceremony to her Indian friends, who at once asked, ‘Why have you not played it that way before? Now it sounds natural!’”

At face value, it sounds like the Native musicians endorsed the harmonized version. But this moment raises a lot of questions. Did it truly sound more natural to them? Or were they responding to the performance as filtered through a Westernized musical setting they were already being exposed to? Or, more critically, is this anecdote serving to justify a creative liberty Fletcher had already taken?

The takeaway is this: while Fletcher’s work was pioneering for its time, it also shows how even well-intentioned scholars can unintentionally reshape and redefine cultural artifacts to fit their own worldview. In harmonizing Indigenous melodies, Fletcher wasn’t just documenting, she was editing.

But Fletcher goes further. In her article “Indian Songs”, she claims that this harmonized form was not only added by her and Fillmore — it was actually preferred by the Native performers themselves:

“The upper line of the score always represents the aria exactly as it was sung; the lower lines the added harmony, which was the particular harmonization preferred by the Indians. The music has not been published in this manner for the purpose of dressing up the melodies, or for the importation into them of any of our own notations; but the songs were the songs of the Indians, and it was deemed proper to print the instrumental rendition of them in the manner the Indians approved.” (Fletcher, “Indian Songs,” p. 93)

This quote feels like a final stamp of approval, as if the harmonization, now justified by Native acceptance, could stand in for the original. But this is precisely where things get dangerous.

This is how history is destroyed by scholarship. When the documentation of a cultural tradition gets filtered through another culture’s lens, even with good intentions, it risks becoming something entirely different. When that version is later cited as “authentic” because a scholar said the original people “approved” of it, you’re no longer looking at the original. You're looking at a constructed image.

Fletcher’s harmonized transcriptions, published and circulated as authentic Native songs, are not neutral records. They are transformed artifacts, shaped by Western ears and cultural assumptions, and then given legitimacy through scholarly language. Over time, this version of “Indian music” replaces the real thing in the public imagination. What we end up with isn’t just an adaptation it’s a copy of a copy, a performance of something that no longer exists in its original form.

In the post-modern philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s terms, the harmonized songs became a simulacrum: a representation that replaces reality with a myth, one that is more “real” to its audience than the original ever was.

It didn’t take long for Native American music to start making its way into popular culture. One reason was Alice Fletcher’s book, which she wrote to help everyday folks and composers better understand and appreciate Native American traditions. Around the same time, Native culture was already gaining attention thanks to Buffalo Bill and his famous Wild West shows. Now, let’s be honest Buffalo Bill loved the spotlight. His version of Native American life was more about putting on a show than telling an accurate story. Even though real Aboriginal people were part of the act, the culture was presented in a way that was more dramatic than truthful, basically, it was entertainment first, authenticity second.

III. Heroes, Villains, and a Manufactured West: The Buffalo Bill Legacy

Buffalo Bill (whose real name was William Frederick Cody) was born in Iowa in 1846. When he was about seven, his family moved to Kansas and started a farm. His dad wasn’t exactly popular in town, mostly because he was strongly against slavery. At the time, Kansas was in the middle of a heated debate over whether it would become a free state or allow slavery. (On a side note, That early exposure to political tension may have shaped Bill’s later decision to include Native Americans in his Wild West shows, giving them a chance to earn a living by performing.)

After the Civil War, in 1872, Cody started working as a civilian guide for both the U.S. Army and the Kansas Pacific Railroad. It was during this time that he earned the nickname “Buffalo Bill,” thanks to his reputation as a top-notch buffalo hunter. He even claimed to have killed over 4,280 bison. Cody also wrote about his adventures in his 1888 autobiography, where he recounted not only his buffalo hunts but also his violent encounters with Native Americans. He published his autobiography alongside stories of frontier legends like Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Kit Carson—figures who, like Cody, helped shape the larger-than-life mythology of the American Wild West.

Buffalo Bill probably first caught the public’s attention in 1872, when he stepped onto the stage in a play written just for him. The show, which was loosely based on his supposed adventures in the Wild West (true or not), was the brainchild of novelist Ned Buntline—who clearly saw a golden opportunity to ride the rising wave of American frontier myth-making. Joining Bill in the cast were Texas Jack Omohundro, one of Bill’s long-time friends, and Giuseppina Morlacchi, an Italian ballerina who would later become his romantic partner. For Cody, this wasn’t just a one-time stunt, it was the moment he caught the “performing bug.” That first taste of the stage lit a spark that would shape the rest of his life, eventually leading to the creation of his above-mentioned Wild West shows.

Bill’s foray into theatre was just the beginning of his rise in popularity. But was it really Bill’s popularity, or was it the growing fascination with Americana? At the time, Americans were still trying to shape a national identity—something that reflected the colonization of the North American wilderness—and Buffalo Bill, along with his frontier adventures, fit that image perfectly. In 1888, Bill decided to publish his autobiography alongside the life stories of three other men he believed represented the spirit of the “Wild West”: Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Kit Carson. In his autobiography, he recounts his life, beginning with the dangerous adventures of his youth—especially his encounters with Native Americans—and continuing through to his later years, including detailed descriptions of taking his Wild West show to Europe and performing for Queen Victoria.

Back in 1883, Buffalo Bill Cody kicked off his legendary traveling show, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, which quickly became a hit across the United States and even in Europe. What made the show stand out wasn’t just the cowboy shootouts and horseback tricks—it was the global flair. Bill added a diverse group of “Rough Riders” from places like Türkiye, Mexico, Arabia, China, and Georgia, turning his Wild West act into more of a cultural spectacle.

One of the show’s biggest moments came at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. That’s where the Wild West really exploded in popularity. The printed program handed out to audiences was massive; it can be found in the collection of in the Library of Congress! This booklet didn’t just list the acts; it dove into the backstories through a mix of history, myth, and entertainment. It even had a section about Native Americans, including a couple of musical phrases from one of their traditional ceremonies.

But here’s where things get tricky.

Buffalo Bill’s show played a big role in spreading the romanticized image of the “Noble Savage.” Native Americans were often cast as the “bad guys” in staged battles where Bill and his cowboys saved the day, whether it was a wagon train under attack or a daring stagecoach rescue.

The irony? The Native Americans playing these roles were actually real Native people. That’s where things start to blur. Philosopher Jean Baudrillard would call this a simulacrum—when the imitation starts replacing the real thing. The line between authentic Indigenous culture and the myth created by the show began to vanish. And unfortunately, for many in the audience, the theatrical version started to feel like the truth.

Continuing with the formation of the Noble Savage antagonist myth, the popularity of the Indian—or “Noble Savage”—carried on through the widely read Dime Novels published in the early 20th century. Once again, we see Buffalo Bill and his companions locked in battles with Indians. It’s in these stories that Native Americans lost any chance of having their culture portrayed with reverence or respect. Instead, the myth was reinforced, pushing aside any real understanding of their heritage.

IV. The Indianist Movement

Alright, let’s get back to the music—because that’s what we’re really here for, right? Not long after Alice Fletcher published her collection of Native American stories and transcribed traditional songs, a wave of composers began to take notice. Inspired by these newly available transcriptions and field recordings from ethnologists like Fletcher, many started writing music that echoed Native American influences. Their goal? To help shape a distinct “American” sound—something authentic and homegrown. This vision sparked what came to be known as the Indianist movement.

To spread this new musical style, one of the leading composers, Arthur Farwell, took matters into his own hands. He founded the Wa-Wan Press in Massachusetts—a publishing company dedicated to promoting compositions rooted in Native American and African American musical traditions. Most of the pieces were written in the light classical style that was all the rage in the early twentieth century. What’s interesting is that many of these Indianist compositions share traits with Fletcher’s arrangements, especially the use of pentatonic melodies and steady eighth-note patterns meant to reflect the drumming in traditional Native performances. Still, these compositions were noticeably westernized, molded to fit the refined edges of the light classical genre. By adapting indigenous music into the familiar structure of light classical composition, composers likely hoped their work would be more easily embraced by the public.

For an example, here’s a link to one of Arthur Farwell’s compositions for piano found in his collections of Omaha songs titled Song of Approach. Op. 21 No.3.

But it wasn’t just classical composers keeping the flame alive. It actually took an entirely different genre to carry the popularity of what was often called “White Indian” music into the mainstream. Enter the Indian Intermezzo—a catchy, pop-inspired style that started popping up alongside ragtime hits and other popular tunes from Tin Pan Alley. These pieces, often written by composers known for their ragtime flair, blended Native American musical elements with upbeat rhythms, making them perfect for the sheet music-buying public of the early 20th century.

V. The "Indian Intermezzo" Phenomenon (1890–1920s)

At the turn of the 20th century, the American public was most familiar with a genre known as “Indian Intermezzi.” As detailed in the article Intermezzi (‘Play It One More Time, Chief’) by William J. Schafer and Johannes Riedel, ragtime composers and music publishers sought to capitalize on the renewed cultural fascination with Native American themes. This commercial interest led to the widespread publication of Indian-inspired intermezzi.

Interestingly, the emergence of this genre began somewhat unintentionally. Composer Charles N. Daniels, writing under the pseudonym Neil Moret, created an intermezzo titled In Hiawatha, inspired not by Indigenous themes directly, but by a train journey through his hometown of Hiawatha, Kansas. The piece gained significant attention, particularly after being performed by Sousa’s Band, and its popularity grew rapidly.

Recognizing its commercial potential, the Whitney-Warner Publishing Company acquired the rights for $10,000. They subsequently enlisted lyricist James O’Dea to add lyrics, transforming the composition into a romantic narrative involving Hiawatha and Minnehaha—figures popularized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 epic poem The Song of Hiawatha. This adaptation marked the official establishment of the Indian Intermezzo as a musical subgenre.

Here’s a link to an original recording of Hiawatha sung by the then popular tenor Harry Macdonough.

At first listen, one might question whether In Hiawatha truly reflects what contemporary audiences would identify as “Indian” music. To modern ears, the piece may not immediately evoke Indigenous musical characteristics. However, for listeners in the early 20th century, subtle elements within the composition began to align with what would later be recognized as the “Indian” musical trope.

For example, when comparing the introduction of Hiawatha to the song Putting on the Insignia of the Thunder God, as published in Alice Fletcher’s ethnographic work, there are noticeable similarities. The rhythmic patterns and the descending melodic contour in both pieces are strikingly alike, suggesting that early composers may have drawn inspiration, whether consciously or not, from Indigenous musical sources documented by Fletcher.

Video: Putting on the Insignia of the Thunder God transcribed by Prof. J. C. Filmore

Although the intermezzo Hiawatha was originally composed to evoke the experience of a train ride, it incorporates several musical elements that were commonly associated with “Indian” music at the time. Notably, the persistent eighth-note patterns in the bass line are intended to mimic Native American drumming, a feature often used to suggest Indigenous musical influence.

Melodically, the piece bears a stronger resemblance to popular cakewalks of the era, reflecting the dance rhythms and stylistic preferences of early 20th-century popular music. However, it is the lyrical content that most directly conveys an “Indian” theme. Despite the musical foundation being rooted in popular forms, the narrative lyrics, referencing the figures of Hiawatha and Minnehaha, were instrumental in framing the piece as “Indian” in the public imagination.

Here’s another neat example of an “Indian Intermezzo” where lyrics were added—just like with “Hiawatha.” This one’s called “Silver Heels,” also composed by Charles N. Daniels (Niel Moret), with lyrics by James O’Dea, published back in 1905. Now, unlike Hiawatha—which was originally written to reflect a train ride, not so much the tender longing of Hiawatha for Minnehaha—Silver Heels was clearly meant to evoke a sense of “Indianness” for its listeners.

Video: Silver Heals sung by Billy Murray (1906)

So, what stands out musically that starts to solidify this so-called Indian trope? First, the melody leans heavily on a pentatonic scale. Then there’s that steady eighth-note accompaniment in the bass line but was pretty common in early 20th-century pop music anyway. And finally, there are touches of open fifths thrown in, used to give off a sense of “primitiveness” that the composer seemed eager to highlight.

Now, what I really want to draw your attention to is that second part of the chorus—the one that kicks off with the word “Silverheels.” If you listen closely to the vocal melody, you can actually catch a glimpse of a popular sports chant. That two-part, downward pentatonic drop? It ends up evolving into the melodies we recognize in both the “Illini War Chant” and the “Seminole Tomahawk Chop.” But there’s more going on here. The melody is accompanied with an early 20th-century hoochie-coochie-esc syncopation, which gives it a kind of playful, seductive rhythm. That choice isn’t just stylistic, it ties into the deeper sexual innuendo woven around the character of Silverheels, who stands in as the stereotypical Native “squaw.” It’s a clear nod to the Native women stereotype that was often exploited and objectified during that time.

Video: Excerpt from Silverheels by Niel Moret (Charles N. Daniels)

In the article by Schafer and Riedel. They make a pretty eye-opening point when they write,

“[The composers] were all skilled in the general trends of the era of ragtime composing, and most popular songs in every genre. Their common bond in the Indian-song movement was an ability to exploit cliches and stereotyped popular conceptions…In short, the Indians of these songs are stock characters from all forms of Victorian popular literature, not at all the products of anthropological research.” (383).

In other words, these composers weren’t drawing on actual Indigenous culture, they were leaning heavily on tired stereotypes and popular tropes of the time. And that’s a big deal when we think about how this “Indian” image, took shape. Since these songs weren’t grounded in any kind of real anthropology, they pushed the portrayal of Native Americans even further from the truth. To be fair, writers like Fletcher and Farwell at least tried to include some background to give their music cultural context, but that was more the exception than the rule. Schafer and Riedel go on to say,

“The lyrics and the music present for the public a comfortably defused and sanitized Indian, a remote figure of pity, a fit subject for charity and compassion (a treatment only possible after the decisive genocidal defeat of the western tribes at Wounded Knee in 1890, when it became clear to the broad public that the Red Menace was totally nullified).” (384).

So yeah, these intermezzi weren’t just catchy tunes. They were part of a bigger cultural shift that turned Native Americans into distant, pitiful figures instead of real people with real histories. The intermezzi were incredibly popular, but they also played a major role in erasing Native identity; something that’s been happening since the very beginning of the United States. These intermezzi played a big role in shaping the early 'Indian sound,' setting the stage for how Native identity would keep being portrayed, though often inaccurately, in other forms of entertainment. Silent films, in particular, ran with these same musical tropes and pushed the simulacrum even further."

VI. Silent Film and the Sonic Stereotype

We now enter the era of silent films—a perfect stage for the 'Indian' genre to take root. It became a setting where Native Americans were slowly turned into museum relics, frozen in time. The music written for these early 20th-century films was cleverly crafted to be super flexible. Composers built pieces with repeatable sections, making it easy for musicians to stretch or shorten the music to match whatever was happening on screen. These scores often leaned on semiotic techniques to support the story, using musical themes to represent characters like the hero, the heroine, or the villain. Common tropes helped define each one—for instance, the villain’s theme might be in a minor key or feature dramatic tremolos to crank up the tension. This added emotional depth through using music’s special relationship to emotions and nostalgia (music’s ability to connect emotions to sounds has been heavily researched) and made the storytelling richer.

When it came to the “Indian” trope, the music usually popped up during scenes of conflict—think cowboy-versus-Indian battles—often under titles like “Indian War Dance” or “Indian Orgy.” The musical elements that signaled “Indian-ness” in earlier “Indian Intermezzi” were carried over into these film scores as can be seen when comparing the following examples with those of intermezzi above. So, when silent film composers borrowed from those intermezzos, they were just extending that trope further into the 20th century. Compositions like these were written as late as 1927!

Video: Indian War Dance by Charles K. Herbert

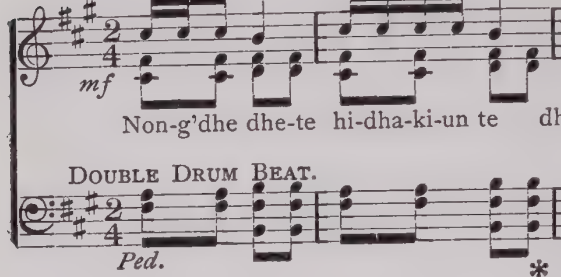

The first example is a piece called “Indian War Dance,” written in 1916 by Charles K. Herbert. It’s an early example of silent film accompaniment composed for solo piano. The music is broken into sections that could easily be repeated or skipped, depending on how long the scene in the film lasted—pretty clever for the time. The melody is based on a minor pentatonic scale, while the accompaniment uses constant eighth-note open fifths, mimicking the sound of Native American drumming that often accompanies traditional singing. (An interesting fact is that in Fletcher’s publication, there is a note to the performer, “double drum beat [sic]” above the bass staff, that the accompaniment that the constant eighth-notes were indeed intended to imitate Native American drumming.)

Excerpt

The melody itself is pretty fragmented, separated by an octave motive that’s decorated with little grace-notes. Rhythmically, it leans heavily on syncopation and features a distinctive pattern of four sixteenth notes followed by two eighths—or sometimes a quarter note—which is a rhythm also found in earlier “Indian Intermezzi.” (See the introduction section in the intermezzo “Hiawatha” above.) As for the dynamics, they remain at a mezzo-forte level. Interestingly, the piece always resolves to the lower note of the octave, and many of its phrases end on the lowest note in the pentatonic scale, giving it a grounded, final feel and that typical melodic descent that was demonstrated in the “Silverheels” intermezzo.

Video: Indian War Dance by Irenee Berge

The second piece, also titled “Indian War Dance,” was composed in 1918 by Irenee Berge. One of the big differences between Berge’s version and Herbert’s earlier one is that this piece was written for orchestra. By the late 1910s and into the 1920s, silent film music was often orchestrated for larger ensembles—basically, the biggest group that could be used to accompany a silent film. It was also a smart move by publishers who wanted to make their compositions accessible to a wider range of performers (and, of course, sell more copies).

Despite the difference in instrumentation, Berge’s and Herbert’s pieces share some key traits. Both use steady eighth-notes in the accompaniment to echo the sound of Native American drumming. They also rely on syncopation in the melody and feature the signature “short, short, long” rhythm that had by then become a defining feature of the “Indian” music trope. This rhythmic pattern had really taken hold by this point in the century, as you’ll notice in these and the following examples, and it didn’t stop there as can be seen by Erno Rapee and William Axt’s piece “Indian Orgy.”

Video: Indian Orgy by Erno Rapee and William Axt

The next piece I want to write about is actually the one that first got me curious about the whole “Indian” trope in film music. It’s called Indian Orgy—and yeah, that title alone immediately hints at the kind of wild, out-of-control image of Native people that silent films often leaned into. With this piece, the 'Indian' trope reaches its most exaggerated and over-the-top form.

Just like Indian War Dance by Bergy, it’s also written for full orchestra, but what really stands out is the massive percussion section: Chinese tom-toms, bass drum, snare, suspended cymbal, triangle, and timpani. That’s a lot more than your standard percussion setup, which usually just includes bass drum, snare, and cymbals.

So why all the extra drums? To me, it’s clear that the composer was trying to signal something intense; something monstrous, even. Rapee and Axt, the composers, were leaning into a musical stereotype that equated heavy percussion with savagery and the so-called “uncivilized.” In fact, they also wrote a piece called Savage Carnival: Wild Man’s Dance (which I’ve blogged about, too) that takes this same approach—lots of drums, lots of primal energy. Another thing that is used the same was as the other pieces I wrote about in Indian Orgy was the use of the pentatonic scale. The main theme starts on the tonic, and descends to the same note an octave below, just like the phrase in Silverheels that I pointed out earlier in the blog. And of course, the syncopation is back in full force. That “short-short-long” rhythm, which emphasizes the second (weaker) half of the measure, shows up in the second half of the first phrase. The overall structure of the piece feels fragmented. You’ve got theme fragments being repeated and developed, which creates this back-and-forth tension between resolution and incompletion. And harmonically? It’s wild—tritones (aka the “devil’s interval”) pop up, along with tons of parallel fourths and fifths. All of this adds to the unsettling, chaotic feel the piece seems designed to evoke.

So, here we are—this is where things have ended up in the long and tangled history of how Native Americans are represented in pop music. They've now been reduced to the image of the savage cannibal. (Back when Christopher Columbus first encountered the indigenous people of the Caribbean, there was already that assumption—they were believed to be the flesh-eaters that old maps warned about, drawn lurking at the edges of the known world.) This image of the cannibal paints Native Americans as monstrous outsiders, pushed to the fringe of society and treated as something less than human. It’s a stark contrast to what Fletcher was working toward in her ethnographic study. Her goal was to present Native cultures as deeply meaningful, complex, and absolutely worth studying and understanding. Nothing like what Axt and Rapee wanted to depict

If you've ever watched a historical movie and thought, “Wow, that felt more real than the real thing,” you’re not alone—and you're touching on something the philosopher Baudrillard talked about. He believed that cinema has a way of taking historical events and turning them into something even more intense, more emotionally powerful, and more polished than what happened. It’s what he called “hyperreality.” Movies don’t just show history, they reshape it, dress it up, and present it in a way that often feels better than the truth. And this doesn’t just apply to film; theatre does it too. We walk away feeling like we’ve witnessed something authentic, when really, we’ve experienced a carefully crafted version of the past. Take “Indian Orgy” as a prime example of creating the hyperreality of the Indian foe. The score ramps up the intensity during scenes of conflict between the “Indians” and cowboys, framing it all like a classic battle between monsters and heroes. The music does a lot of the heavy lifting here, with its jarring, disjointed phrases, the use of the pentatonic scale, an aggressive percussion section, and those repeated fifths mimicking tribal drumming. All of it comes together to create a soundscape that signals to the audience: these “Indians” aren’t just opponents, they’re frightening, monstrous figures from beyond the borders of safety. (I write more about the otherness of monsters and Monster Theory in my “Savage Carnival” post.)

The next example is another noteworthy “Indian War Dance,” composed in 1927 by the British composer Joseph Engleman. Engleman was recognized for his work in the light classical genre, frequently composing for light entertainment, including ballets and film scores throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Given its composition date, coinciding with the end of the silent film era and the emergence of “talkies” in 1927, and its British origin, this piece offers a clear example of how elements of the “Indian” trope had become entrenched in music associated with film and theatrical productions during that period.

Video: Indian War Dance No. 15 by Joseph Engleman

Scored for a small orchestra, which was typical of the time, the piece includes several musical features that illustrate the ongoing use and solidification of the “Indian” stereotype. Among these are the short-short-long rhythm (and its variations), which emphasize the second beat of the measure—a rhythmic trait also found in the so-called “monster” trope. The work also employs pentatonic scales and a steady eighth-note rhythm meant to evoke Indian drumming. A particularly distinctive feature of this composition occurs toward the end of the B section (in C major), where the first violins vocalize an “ah” on a dotted-quarter-note/eighth-note motive. Due to the use of parallel fifth motion in this passage, it produces what was perceived at the time as a distinctly “Indian” sound.

Engleman, being outside of American culture, likely knew of Indigenous peoples only through what he saw in TV shows and movies. That makes his use of the “Indian” trope especially telling. The musical traits mentioned above that are tied to this stereotype had become so strong—so deeply rooted in popular media—that they showed up in his work, even though he was far removed from the culture that originally created the trope. By the time Engleman composed this piece, the trope had become just that: a hollow shell. He didn’t need any firsthand knowledge of Indigenous cultures to use it. The trope had evolved to the point where authenticity was no longer required. This also speaks to the later stages of Baudrillard’s idea of the simulacrum—the point where a representation masks the fact that there’s no real meaning behind it anymore.

As outlined in the introduction, my engagement with the “Indian” trope began during my study of silent film scores. It was Rapee and Axt’s Indian Orgy that first piqued my interest, as its striking similarity to the “Tomahawk Chop” suggested a possible historical connection between the two. This discovery prompted me to investigate how such a trope developed and circulated across cultural forms. Interestingly, my initial research into the trope’s presence in sports did not begin with chants or stadium anthems but rather with a cartoon theme song that remains surprisingly recognizable to modern audiences.

VII. Echoes in Sports

You ever notice how that “war chant” tune you hear at football games sounds oddly familiar no matter the team? That’s because it kind of is the same song—just recycled, repackaged, and replayed across sports and decades. It traces all the way back to a 1950 cartoon song called Pow Wow by Monty Kelly, which had this tribal-sounding beat and a super simple, pentatonic melody that folks labeled as “primitive.” From there, it morphed into a marching band piece at Illinois State in the '60s, then into the Illini War Chant in the '70s and eventually got adopted (and made famous) by Florida State students in the '80s. By the '90s, you had the Atlanta Braves and Kansas City Chiefs doing the Tomahawk Chop with the same exact melody. One tune, a dozen versions, and over a century of echoing through stadiums. Kinda wild how one cartoon theme song basically became the DNA of sports “war chants,” huh?

Let’s dive into this a bit more. As we mentioned earlier, the very first version of what eventually became known as the “Tomahawk Chop” actually started with the theme song from a quick five-minute cartoon. This cartoon aired during the popular kids’ show Captain Kangaroo, which, fun fact, was one of the longest-running children’s programs, airing from 1955 all the way through 1984. What we’re really homing in on here is the opening phrase of that 1950s theme song, composed by Monty Kelly. Give it just one listen, and it’s pretty clear, this tune lays the groundwork for the pentatonic melody we now recognize, especially with that “Silverheels” motif we highlighted earlier. But it’s not just the melody that grabs your ear. Alongside the simple, “primitive”-style pentatonic line, you’ll also notice a few musical cues that have become almost cliché in their association with this trope—like the ever-present “Indian Drum” backing and the signature “short-long” rhythmic pattern.

Video: Adventures of Pow Wow: Playn’ Possum

The first instance of “Indian” trope in college sporting events takes place at Florida State University in the 1960s. Their mascot, Osceola, and the team’s identity as the Seminoles, were rooted in imagery drawn from the Native American tribe native to Florida. Osceola was introduced as a symbol of bravery and warrior spirit, aligning with the school’s broader representation of the Seminole legacy. Since FSU embraced a Native American figure as a central part of its athletics identity, the accompanying music was designed to match, crafted to evoke what was then considered an “appropriate” musical expression of “Indian-ness.” A prime example of this was a piece bluntly titled Massacre. And yes, the name alone raises eyebrows. The piece leaned hard into the well-worn “Indian” music trope: a repetitive eighth-note drum rhythm driving the beat, paired with a so-called “primitive” pentatonic melody. That melody was harmonized in parallel fifths and fourths—a musical technique that also appeared in the Axt and Rapee piece Indian Orgy, which we mentioned earlier.

Video: FSU Massacre rallying tune.

In the 1970s, the beginings of the “War Chant” that is so popular now days, surfaced at Illinois State University. This version closely resembled, almost note for note, the theme song from Pow-Wow the Indian Boy, even sharing the same key. The musical traits associated with the “Indian” trope were once again clearly present, including the familiar drum patterns and pentatonic melodies.

Video: Illini War Chant

Approximately a decade later, in 1983 and again in 1985, Florida State University adopted the Illini War Chant and, through a somewhat ambiguous creative process, developed what is now known as the Tomahawk Chop. Upon closer analysis, the Tomahawk Chop appears to be a blend of the Illinois War Chant and FSU’s Massacre. The pentatonic melody, which is unmistakably based on the Illini War Chant with slight variations in rhythm and pitch, is complemented by harmonization in open fifths, a stylistic feature derived from the Florida Massacre.

Video: FSU Football Chief Osceloa Renegade at Doak Tomahawk Chop

In the early 1990s, the influence of the Tomahawk Chop extended from college into professional sports. It was adopted by the Atlanta Braves in 1990, becoming widely used at their games to energize fans. The following year, in 1991, the Kansas City Chiefs also embraced the chant, further cementing its presence in American sports culture.

As of this writing, some sports teams still use “Indian” mascots, while others have reduced or eliminated them. Although the Braves continue to use the team's name, which dates back to 1912 and has remained unchanged through moves from Boston to Milwaukee and finally Atlanta, they have faced growing scrutiny over their encouragement of the Chop. After public backlash, especially from Native American groups, the organization has scaled back its official promotion of the chant multiple times. In 2019, for instance, the Braves suspended distribution of foam tomahawks and paused playing the Chop music during a National League Division Series game in response to criticism from Cherokee Nation pitcher Ryan Helsley. While MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred has affirmed that the Braves have done well in their consultation with the Eastern Cherokee Band of Indians, the team has clarified that there are no plans to change their name—but they continue evaluating the chant's future in collaboration with tribal leaders and fans.

In contrast, the Kansas City Chiefs have continued to use the Tomahawk Chop during games, along with other related fan traditions. While the team has made some symbolic gestures—such as discouraging fans from wearing headdresses or face paint—they have not removed the chant itself, and it remains a prominent feature at Arrowhead Stadium.

Sadly, the Tomahawk Chop along with the university’s mascot, is still being used at FSU sporting events.

The Cleveland Indians, on the other hand, has changed their name to Guardians in 2021 and in the NFL, the Washington Redskins, a name that is considered to be discriminatory by many, has changed their name to the Commanders in 2022.

So, in the end, it’s important to recognize that the “Indian” trope, as we know it, has largely been shaped, if not entirely produced, by White cultural and representational practices, and it stretches back to at least the early twentieth century, beginning with Alice Fletcher’s publication of “Indian songs” that were reinterpreted through Western-style harmonization. Since then, the formula has remained strikingly consistent. For example, the university “war chants” featured above, often include an “Indian drum” accompaniment and a variation of the “Pow-Wow” melody, with some even layering in open fifths for harmonization. These musical features have been frequently, and currently, presented as “authentic” Native American music, but that claim reveals a deep misunderstanding of Indigenous musical traditions, which are far more complex, diverse, and culturally specific than these stylized imitations suggest.

How did the “Indian” trope evolve into what we see today? More specifically, how did early field recordings by researchers like Fletcher eventually give rise to sports chants that rely on harmful stereotypes of Indigenous culture? To explore this question, it’s helpful to turn to a philosopher who has examined such processes in depth. Jean Baudrillard, a French theorist, developed the concept of simulacra and simulation, a framework that can shed light on how tropes function. (Tropes, in this context, can be understood as a series of simulations that share recognizable features and are collectively identified as a single idea.) Through Baudrillard’s lens, we can begin to understand why these chants are entirely disconnected from authentic Indigenous culture. What does Baudrillard say about this and let’s relate it to the “Indian” trope.

VIII. Conclusion

Baudrillard’s Four Phases Applied to the Chop

When Real Becomes Representation: The Process of the Simulacrum

Let’s talk about how something real slowly becomes... not so real. In philosophy, this is what Jean Baudrillard calls the process of the simulacrum, and honestly, it’s a fascinating way of thinking about culture, identity, and how we represent things.

Phase One: A Reflection of a Profound Reality

In the beginning, we have the real thing. In our case, it’s the field recordings made by Fletcher and others of native music that I mentioned in this post: raw, authentic, captured in its natural context. At this stage, the representation still points back to a deep, meaningful reality. You can listen to the recordings and get a direct understanding of what it is. There’s nothing in-between that’s blocking the experience of the music. It’s a reflection, not a distortion.

Phase Two: Masking and Distorting the Real

Then comes the second phase. Now, the original is still there, but it’s being tweaked—think of Fletcher’s compositions that she published in her book or the harmonizations done by the Indianist composers wrote for the Wa-Wan Press. These are built from authentic sources, the transcriptions of live performances or of recordings, but they smooth the edges, make the unfamiliar sound familiar by adding western style harmonization, and in doing so, they begin to mask and denature the original music. The representation is now stylized, filtered through another cultural lens. Through the lens of western aesthetics and begins the separation of indigenous culture from the music.

Phase Three: The Illusion of Reality

By the third phase, we start seeing things like “Indian Intermezzi” and later on the silent film compositions. Here, the DNA of the music, the core traits, the pentatonic scales, rhythms, and the native drumming, are extracted and rearranged for a more general public. It’s like using the idea of Native music without grounding it in any lived, cultural truth. Even though the first Intermezzi were not intended to replicate native music, there were enough of the traits in the music to identify them as “Indian.” The result? A mask of a mask. It pretends there’s a real behind it, but there isn’t. It’s a mirage of authenticity.

Phase Four: The Pure Simulacrum

And finally, we reach the simulacrum in its purest form. Think “Tomahawk Chop,” the Disney version of the “Indian” trope, and other chants at sports games or the generic “Native” themes you hear in cartoons. These aren’t reflections or distortions of a reality; they have no connection to it at all. They’ve become their own thing entirely. This is very evident in the fact that the “war chants” used at the sporting events are all very closely related to each other using the same basic features (pentatonic melody, harmonized by open fifths, percussion performing the “Indian drum” eighth-note rhythm) they’re Disney versions of Native music, for example, they feel familiar not because they’re authentic, but because they recycle the same codified DNA of the trope over and over again.

Reproducing the Simulation: The Echo Chamber Effect

Now here’s where it gets even wilder. These simulations don’t just sit there, they get reproduced. The sports chants are a prime example. But the reproductions aren’t going back to the original culture or sound. They’re copying the simulation. They’re built from a “DNA” that’s already been deemed correct for representing whatever idea of “Indigenous music” people have come to expect.

These new versions? They’re true simulacra. They don’t point back to a reality—they’re spinning in orbit around a cultural nucleus made up of assumptions, stereotypes, and artistic shorthand. If they ever broke away from that DNA, they’d stop “making sense” to the people listening. They’d lose their meaning, their recognition factor.

Playing Indian by Philip J. Deloria is an essential resource for anyone seeking to better understand the complex history between white settlers and Indigenous peoples. In the book, Deloria explores how white Americans have appropriated and reshaped “Indian” identity—beginning before the American Revolution and continuing throughout the nation's history to the present day. This work significantly expanded my understanding of that relationship, especially considering how little of this history was covered in the public schools I attended. Two chapters, in particular, offer valuable insights into how white individuals appropriated and utilized "Indian" identity during the 20th century, making them especially relevant to the arguments presented in this article.

Philip Deloria: Playing Indian

Deloria argues in his book Playing Indian (1998) that, throughout U.S. history, settlers have repeatedly appropriated Indigenous culture as a way of shaping their own sense of American identity. In his book, he notes that Americans have, decade after decade, “dress[ed] up [as Native Americans] and act[ed] out their ideas, making them material and real, and shap[ing] new identities in the process… over and over again.” In the early 20th century, this process was informed by the Recapitulation Theory, which framed settlers’ relationship to Indigenous culture. By the latter half of the century, however, Indigenous identity became more commonly associated with ideas of nature and ecological wisdom—a shift that is especially relevant to the concerns of this article.

Historian Philip Deloria explains that around the start of the 20th century, American identity started to shift. Characters like Davey Crockett and Daniel Boone weren’t just frontier legends anymore they became symbols of a new kind of masculinity. With the rise of industrialization and rapidly growing cities, many people believed society was becoming too mechanical, too tame. There was a growing fear that modern men, working desk jobs in urban offices, were losing their grit and independence; essentially being feminized. This was especially true as they were increasingly seen as just cogs in a system designed to benefit wealthy business tycoons, men who exploited workers to generate even more profit for themselves. In response, there was a push to educate boys by teaching them how to survive in the wilderness. This type of education was seen as a way to guide children through the stages of human evolutionary development, and part of that process included encouraging them to emulate Native Americans—who were believed to represent the adolescent stage of humanity. This belief was rooted in the archaic idea, known as Recapitulation Theory. This philosophy believes that cultures evolve in phases, like individuals, moving from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. And Native cultures were thought to be stuck in the adolescent phase. By imitating these so-called "adolescent" behaviors, children could be prepared for entry into the fully developed, adult stage of modern civilized life. This theory, asserted by the psychologist G. Stanley Hall (1844-1924) even helped fuel the founding of early scouting organizations, which aimed to instill frontier values, physical toughness, and moral uprightness in young boys.

The use of the “Indian” mascot can be better understood when viewed through the framework of recapitulation theory. This theory posits that stages of individual learning mirror broader stages of human development. In this context, college was often framed as the final stage of formal education before an individual entered the workforce and assumed adult responsibilities. Administrators, therefore, may have selected the “Indian” as a symbol of this transitional process, equating the intellectual and social development of students with qualities they associated—however problematically—with Indigenous peoples. In this way, recapitulation theory served as a justification for adopting Native American imagery in collegiate mascots.

Recapitulation theory helps explain why colleges adopted “Indian” mascots in the early twentieth century, but the rationale shifted in the later decades. As Deloia observes, the image of Indigenous peoples changed during the 1960s and 1970s: they were no longer framed primarily as “primitive,” but instead idolized for their perceived closeness to nature. Within the countercultural movements of this era, Native Americans became symbols of authenticity and resistance to mainstream society. In this context, “Indian” mascots could be understood as serving a new symbolic role—as a cultural bridge between white settlers and Indigenous peoples.

This dynamic is evident in the case of Florida State University, where members of the Seminole tribe “authenticated” the mascot by creating a costume. On the surface, this may appear to legitimize the representation. However, as Deloia points out, the irony lies in the fact that Native Americans were effectively endorsing a figure that historically embodied settler fears of Indigenous “monsters.” By contributing to the construction of the mascot, the Seminoles were, in effect, saying: “Your imagined monster is not authentic enough; allow us to refine it.” The act thus highlights the paradox of Indigenous involvement in reproducing the very stereotypes that once dehumanized them.

The “Tomahawk Chop” is not an echo of Indigenous survival, but rather a performance rooted in illusion, a cultural hallucination born from settler nostalgia and sustained through generations of mediated reinterpretation, or in other words simulacra as described by Baudrillard. From the early ethnographic work of Alice Fletcher to the contemporary spectacle of sports fandom, we witness not a preservation of Native identity but the continuous erasure and replacement of it with simulations that serve non-Native desires. The image of the “Indian” has long been entangled with constructions of primitivism, savage masculinity, frontier nostalgia, and longing for an American authenticity; all of which are ironically manufactured and staged by those outside the culture they claim to represent.

As the figure of the Native vanishes from lived experience, it is the settler who steps into the costume, assuming both the symbolism and the performative rights to Indigenous culture. In the case of Florida State University, and the Kansas City Chiefs, it is the white settler who dons the "Seminole-approved" costume of the school’s mascot, embodying and perpetuating a settler-constructed symbol of so-called primitive (or “savage”) masculinity, a caricature that reflects colonial fantasies rather than authentic Indigenous identity. This process, which began as a mediated interpretation, has culminated in a spectacle that no longer gestures toward reality at all. The “Tomahawk Chop” is not a tribute; it is a simulacrum, one that tells us more about white America’s fantasies than about the cultures it purports to honor.

It is time to critically interrogate these soundscapes and performances in our public arenas. We must rethink the ethics of cultural representation and ask ourselves: what is truly being celebrated, and at whose expense?

Sources

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. University of Michigan Press, 1994. First published 1981.

Deloria, Philip J. Playing Indian. Yale University Press, 1998.

Fletcher, Alice C. “Indian Songs and Music.” The Journal of American Folklore 11, no. 41 (Apr.–Jun. 1898): 85–104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/53321.

Fletcher, Alice C. Indian Story and Song from North America. Small, Maynard & Company, 1907.

Schafer, William J., and Johannes Riedel. “Indian Intermezzi (‘Play It One More Time, Chief!’).” The Journal of American Folklore 86, no. 342 (Oct.–Dec. 1973): 382–87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/539362